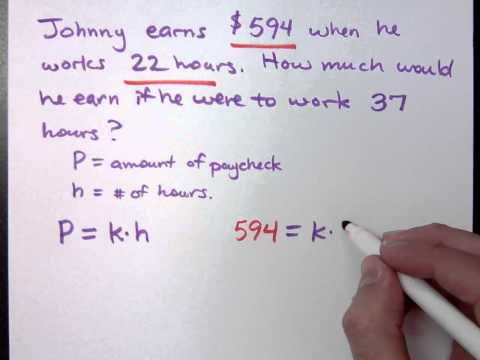

More general variable-endpoint problems in which the initial point is allowed to vary as well, and the resulting transversality conditions, will also be mentioned in the optimal control setting (at the end of Section 4.3). The transversality condition itself isĮssentially a preview of what we will see later in the context of Techniques again soon when deriving conditions for strong minima In the specified form requires a somewhat more advancedĪnalysis than what we have done so far. Working on this exercise, the reader will realize that Perturbation family which allows us to obtain one extra condition ( 2.27). Have only one endpoint fixed a priori, but on the other hand we have a richer The integral I(y) is an example of a functional, which (more generally) is a mapping from a set of allowable functions to the reals. With the Basic Calculus of Variations Problem, here we A typical problem in the calculus of variations involve finding a particular function y(x) to maximize or minimize the integral I(y) subject to boundary conditions y(a) A and y(b) B.

We can think of ( 2.27) as replacing the boundary conditionīoundary conditions to uniquely specify an extremal. The resulting family of curves is depicted in Of the curve is still fixed by the boundary condition Suppose that the cost functional takes the same form ( 2.9) Necessary conditions and the validity of. Perturbations will also change, and in general the necessary condition for Key words and phrases: regularity of solutions, Lagrangians, EulerLagrange equation. If we change the boundary conditions for the curves of interest, then the class of

The first-order necessary condition ( 1.37)-which serves asįor the Euler-Lagrange equation-need only In ( 2.11), was explicitly used in the derivation of the Euler-Lagrange We do it in several steps: One-dimensional problems P (u) 0) dx, not necessarily quadratic R F (u u Constraints, not necessarily linear, with their Lagrange multipliers Two-dimensional problems P (u) RR F (u ux uy) dx dy Time-dependent equations in which u 0 dudt. Is restricted to those vanishing at the endpoints. Even more remarkably, problems which don’t look at all like least-time problems can usefully be reformulated in this way. This program carries ordinary calculus into the calculus of variations. Accordingly, the class of admissible perturbations The curves have both their endpoints fixed by the boundaryĬonditions ( 2.8). So far we have been considering the Basic Calculus of Variations Problem, in which The following problems were solved using my own procedure in a program Maple V, release 5. The problem above can be seen as an optimisation problem in inn-itely many variables (one for each t t 0,t 1). Next: 2.4 Hamiltonian formalism and Up: 2.3 First-order necessary conditions Previous: 2.3.4 Two special cases Contents Index Calculus of Variations solved problems Pavel Pyrih J( public domain ) Acknowledgement.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)